Soy emo ¿y qué?

On the emo march of 2025, reviled Mexican subcultures, and more notes from the mental miscellanea.

Every year, there will be one day in March that intimates what spring will look like in Mexico City. The temperature jumps above 80 degrees in the hours between 11 AM and 1 PM –– a dry heat amplified by a surplus of pavement. While most of the City’s flora thirsts for rain that will not come for another four months, purple cherry blossoms or jacarandas miraculously surface, adding a hint of technicolor to the dusty haze.

On an unusually clear day, before everything was subsumed to grey, CDMX residents were called to assemble for two distinct reasons. The first was a national day of mourning, a funeral-like procession to honor the victims of the mass-crematoriums found in the state of Jalisco and to denounce government impunity and/or government complicity in the country’s death machine. The second was an invitation to participate in the first commemorative emo march, set to the tune of My Chemical Romance’s “Welcome to the Black Parade.”

The former was speckled with grass-root leaders, candles, abandoned shoes (echoing the images of what was left behind in the crematorium), self-funded sleuths, and mothers that search for the disappeared. The latter was filled with teenagers, their parents, and a few people in their late thirties looking to mosh in an homage to the country’s once most reviled musical subculture.

On that Saturday of conflicting national agendas, I attended the 2025 emo march.

“Soy emo, ¿y qué?” ("I’m emo, so what?")—this phrase could be read on dozens of posters at the Glorieta de Insurgentes on Saturday, March 14, 2025. Under jacaranda trees, two massive Beyoncé billboards, and a permanent public exhibition “showcasing women's contributions to Mexico and giving voice to their thoughts,” hundreds of self-proclaimed emos, hybrids of emos and punks, and even a few furries emerged en masse from an underground staircase.

With pink hair, Jack Skellington-style tights, skinny jeans, side-swept bangs covering half their faces, and legendary band T-shirts, the emos took over the Glorieta de Insurgentes with a jubilation worthy of a national holiday—because for this subculture, relegated to myth, it was.

The pilgrimage began in front of the marbled Beaux Arts building at 1:00 PM, and marched through Avenida Juárez and Reforma until reaching Insurgentes, a storied watering-hole for the city’s alternative crowd. Instead of carrying Virgin of Guadalupe banners, as it’s usually done during high-national holidays, the emos waved white flags featuring two cartoon figures surrounded by purple hearts that read "EMO MARCH" and "emo love."

As I wandered through the forum, I took refuge from the sun in the shops selling exotic lingerie and bedazzled jock-straps. From there, I saw purple smoke covering the plaza and heard a pained sing-a-long that overpowered a makeshift sound system, barely held together by small Bluetooth speakers. Amidst this buffet of curiosities, surrounded by hundreds of posters boldly declaring "I’m emo, so what?" I was on a mission to understand: what does it mean to be a Mexico City emo in 2025?

Here’s what I heard:

"Being emo is an aesthetic that goes against what’s normal," said Noa, 17.

"[Being emo] is embracing emotional vulnerability," said Adriana Campos, 21.

"[Being emo] is adapting to having a bad time," declared Jesús, 32, laughing after being interviewed by TV Azteca’s Venga La Alegría, one of the most popular variety shows in the country.

The term "emo"—whether it’s deployed as a concept, a feeling, or an identity—is no longer neologistic in Mexico City’s vocabulary. On the contrary, an “emo” is an icon of Mexico City’s history, the subject of countless memes, school monographs, and even an episode of the popular podcast Radio Ambulante, back when it was produced by NPR.

The story traces back to March 16, 2008, when hundreds of emos assembled at the Glorieta de Insurgentes in downtown Mexico City for a rally. In the weeks leading up to it, rockabillies (!), punks, and goths had taken to social media platforms like Facebook and Myspace (RIP) to threaten an ambush. Yet, despite the online intimidation, the emos stood their ground, arriving in full force to confront their would-be attackers.

Despite sharing the same spaces—like the Glorieta—fashion, and even musical tastes, rockabillies, punks, and goths had a problem with emos. "We are against emos," a punk told a TV reporter that day. "[We’re attacking them] because they’re copying our style."

As expected, a group of punks and their allies showed up at the Glorieta, prepared for a fight. The clash ignited when an emo swung a belt, quickly escalating into an all-out brawl. Nearly a hundred police officers were dispatched to contain the chaos. In a scene straight out of a surrealist film, the only ones who managed to restore order were a group of Hare Krishnas, weaving through the crowd with drums and chants.

Gabriel, 36, was at the Glorieta that day, representing the emo side. This past Saturday, he wore a T-shirt featuring the famous meme where a photograph of emos replaces Antonio González Orozco’s artwork of Benito Juárez on the cover of the government’s fifth-grade history book. Gabriel is one of those emos forever trapped inside that iconic orange frame. Though he’s no longer a full-time emo —most of those in attendance weren’t even born in 2008—he fondly remembers his youth and describes the emo group of that era as a "brotherhood," a collective of "lost teenagers" who "embraced each other." "For me, being emo will always be synonymous with being real," he told me.

Across the Glorieta, a couple and their daughter held a sign reading "Being an emo family is the best!" They wore coordinated outfits: fishnet stockings, striped shirts, and a chessboard-print dress. Mariana, now 25, attended the first emo march in 2008 with her father when she was just 8 years old. Now, she brought her 9-year-old daughter, Melanie (who was cosplaying as Paramore’s Hayley Williams), to share the experience. Around them, both teenagers and thirty-somethings dressed almost identically as they did in 2008. The only sign of time passing came from a phrase painted on a forty-something year-old man’s jacket that read "It wasn’t a phase, Mom."

The 2025 emo carnival does not seem like a subversive proposition, and the emos’ insistence on labeling themselves as such verges on the anachronistic, almost corny. But I remember when being emo meant being a cultural outcast – an individual that provoked moral panic simply by parading their aesthetic in public. A poll conducted in 2008 revealed that 54% of Mexico City residents were very or somewhat intolerant of emos and 48% of those surveyed believed that parents of emos should "guide" their children to change their appearance.

Unlike Americans who saw emos flourish in physical and digital spaces during the heyday of LiveJournal, Myspace, Warped Tour, and Fueled by Ramen bands, Mexico City had a legitimate emo problem that became a cause for national concern. After years of conducting research (aka being a journalist) and empirically approaching Mexico’s obsession with the New York band, Interpol, I have come up with a few theories:

Emos were extremely online. If you’re an ethnomusicologist or a purist, you’ll know that emo as a musical genre is a pre-internet medley of post-hardcore and late 1980s punk. Nonetheless, emo as an aesthetic didn’t become widely adopted until the mid-2000s, when emerging internet personalities (i.e. Jeffree Star, Juliet Sims) found an audience in emerging internet platforms (i.e. YouTube) to promote their music, lifestyle, and show off their sick fits. To be an emo anywhere meant being versed in a blooming digital language that circumvented borders and cultural norms. In other words, Mexican emos were spending a lot of time online and participating in internet communities that eschewed “traditional Mexican values.”

Emos were not part of a political project. For decades, Mexican punks and rockabillies have been cast as respectable subcultures. According to Pacho Paredes of the Mexican rock band, Maldita Vecindad, rock music played an important role in Mexico’s political and social liberation1, especially during the country’s single-party rule. Interpol's popularity as a rock band may fall under this historical logic. Unlike punks who stuck-it-to-the-man or the city’s cumbiamberos who were aggressively proletariat, underneath the sheen of the sentimental pop-punk and screamo that emos listened to, there was no clear political vision.2

Emos never “became Mexican.” Sonideros are Mexican. But do you know who else is Mexican? Morrissey3 and Paul Banks and perhaps even Robert Smith. Some bands live long enough to become Mexican bands, and others, like My Chemical Romance, fade to the recesses of memory before that happens. Of course, there were Mexican emo bands such as PXNDX, División Minúscula, and Allison, but most were considered derivatives of their American counterparts.

In Subculture: The Meaning of Style, cultural historial Dick Hebdige illustrates how subcultural style (which he describes as "expressive forms and rituals of subordinate groups") can be perceived as a threat to public order or dismissed, denounced, or even canonized. Hebdige dedicates most of his semiotic analysis of style to the punks, teddy boys, and of the UK, but his framework is nonetheless useful to understanding emos' role in Mexican public life. According to Hebdige, subcultures cobble together (or hybridize) styles out of the images and material culture available to them in the effort to construct identities that are ostensibly defined against other cultures and groups.

In Mexico’s musical, cultural, and sonic imaginaries, emos emerge as a rare creature, totally unconforming to the country’s national mythology. Inasmuch as Mexicans pride themselves on their love for rock and punk music, these tastes only appear subversive to an outsider (usually a foreigner) who has different expectations for what Mexicans should listen to. Otherwise, punk and rock are, within the so-called subcultural scheme, totally hegemonic. Using Hebdige’s logic of subcultural style, emos are the country’s unlikely totems of stigmata. So much so that the quasi religious telenovela, La Rosa de Guadalupe, has dedicated two episodes to emos, casting them as spiritually corrupt individuals that require divine, miraculous intervention in order to survive.

After nearly two decades of stigma, the Mexican emo is beginning to live out its canonical arc. At 3:30 PM, the first mosh pit erupted to the sound of Taking Back Sunday’s "Cute Without The E." Minutes later, plastic bottles and Little Caesars pizza boxes started flying, recreating a familiar scene. But this time, there was no fight— and there were no aggressors. It was almost a performance. At the edge of the human whirlwind, a Hare Krishna circled the public plaza. When I approached him for an interview, he simply gestured with the hand that wasn’t operating a miniature cymbal. He had taken a vow of silence.

Notes from the mental miscellanea:

Next week, the grace period for tariffs on Mexican goods will expire, leaving Mexican president Claudia Sheinbaum to work more magic. The wishy-washy tariff war with Mexico could be a way for both Trump to make good on his campaign promises and for Sheinbaum to emerge as the region’s strong-woman. This is a good rallying cry for both of their bases, but the real consequences could still be catastrophic, according to experts, of course.

The Federal Institute for Access to Public Information and Data Protection in Mexico was shuttered three days ago, but the government assures that transparency won’t be eroded. Okay!

I’m a sucker for anything that is cumbiafied or Mexican-regional-ified, which is why I’ve been bumping EZ Band’s norteño cover of “Linger” and Grupo Klas Y Keroz’s cover of “Big in Japan (Solo en Japón).”

“Awful in such a novel way:” Max Read’s most recent podcast with Sam Biddle on the applications of AI was great.

Next on Vita Chronicles

Claudia Sheinbaum’s jewishness or lack thereof was a sticking point during her presidential campaign – but only among American onlookers. Over the past weeks, I’ve been revising an essay I originally wrote in 2023 about Jewish immigration to Mexico and what that tells us about the Inquisition, the country’s complicated founding mythology, and why one of Mexico’s oldest synagogues is modeled after one in Lithuania.

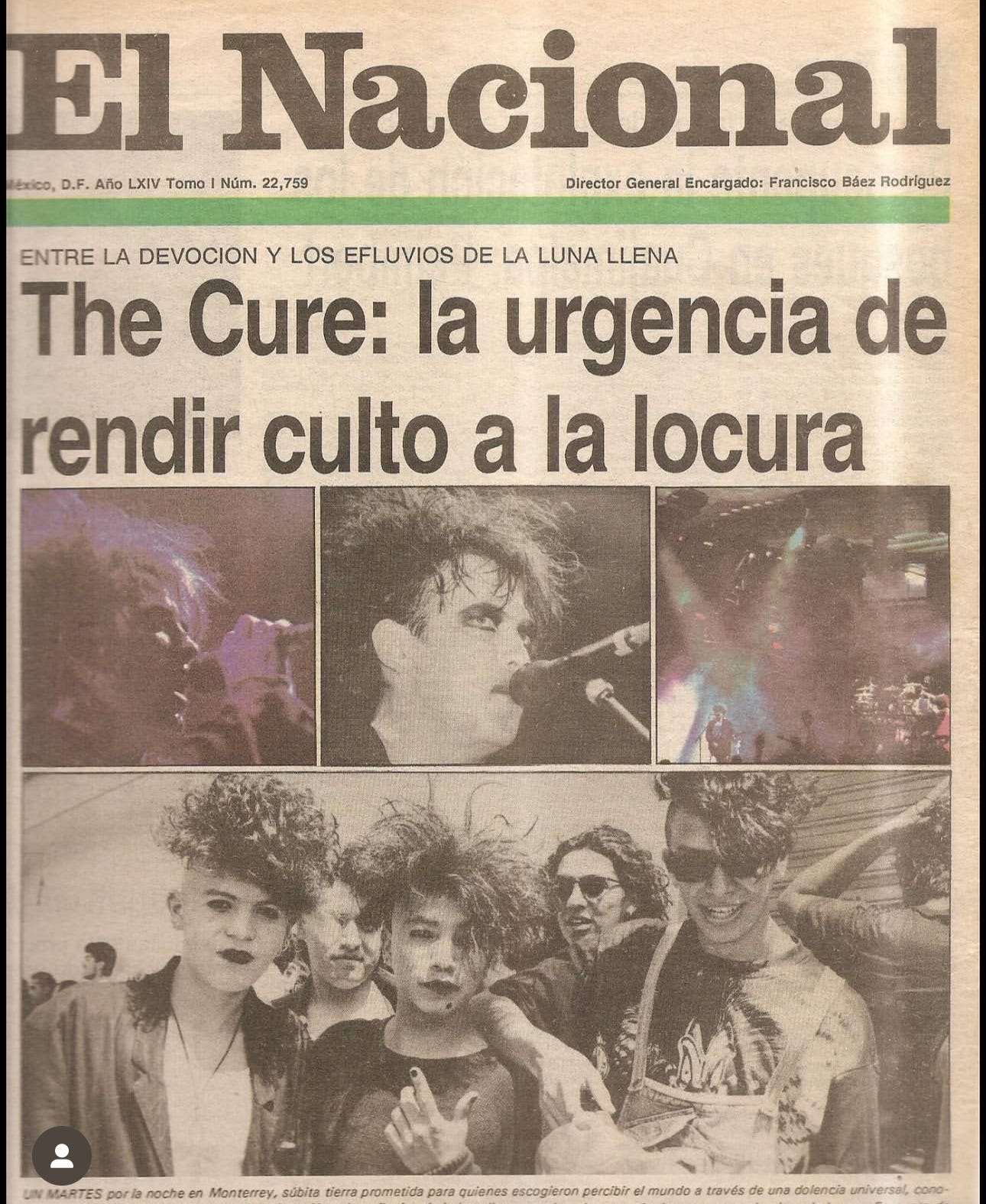

Until next time, here’s the front-page of a newspaper when The Cure first toured Mexico.

Vita

Interestingly, Mexicans are also really weird about reggeatón.

Emos were nonetheless subversive in their gender presentation, which challenged conventions imposed by the Catholic ruling party at the time. In this sense, I do believe that that emos were somehow politicized, but not in ways that Mexicans were used to seeing.

In spite of who Morrissey is, he is one of Mexico’s most adored musicians. In 2016, Mexrrissey, an all-star Mexican Morrissey cover band released their only LP to date, “No Manchester” — an absolute Spanish-language banger rendition of Morrissey’s greatest hits.

“The Federal Institute for Access to Public Information and Data Protection in Mexico was shuttered three days ago, but the government assures that transparency won’t be eroded. Okay!” This really made me chuckle. Love it, Vita!